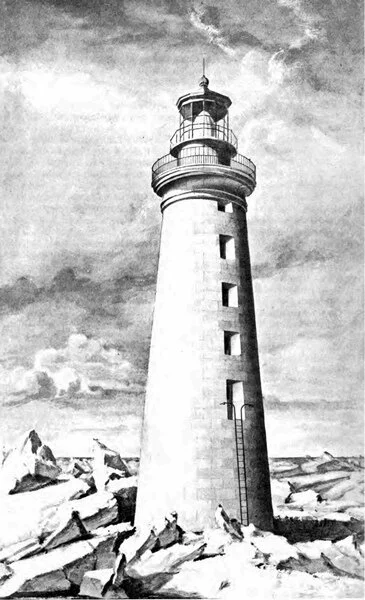

Original Design of

Spectacle Reef

Location

Northern Lake Huron

Coordinates

45°46′24″N 84°8′12″W

Start of Construction

1870

First Year in Service

1874

Automated

1972

Tower height

97 feet (24 m) from Reef

Focal height

86 feet (26 m)

Original lens

Second-order Henry-Lepaute Fresnel lens; alternating red and white flashes every 30 seconds (30 seconds darkness, white flash, 30 seconds darkness, red flash, repeat).

Current lens

Solar powered 300mm Tideland Signal acrylic lens

National Register of Historic Places

Site #05000744.

The History of Spectacle Reef

The story of Spectacle Reef Light Station begins thousands of years ago when the area it now marks was first formed. The reef is comprised of two limestone mounds in close proximity to each other that are connected by a slightly deeper ridge, the remains of an ancient mountain that once rose out of the bottom of the lake. Over time erosion and rising lake levels caused this mountain to slowly disappear below the surface of Lake Huron and forming a reef that was “more dreaded by navigators than any other danger unmarked throughout the entire chain of Lakes” and lurked only four feet below the surface of the lake in some areas. These two shoal areas with the ridge resemble a pair of eyeglasses when viewed from above, hence the appropriate name “Spectacle Reef.”

For years mariners and shipping companies asked for Spectacle Reef to be marked. The reef was located at the crossing of multiple shipping lanes through the Straits of Mackinac and at a point where waves had a fetch of 170 miles. This meant any vessel that got to close to the reef in any kind of seas would surely bottom out and potentially wreck. Congress began conversations about marking the reef in the early 1850’s with a buoy first being placed in 1856, but the onset of the American Civil War put a halt to any funds being used for lighthouse construction. In the fall of 1867 two vessels, the Annie Voight and the Alice Richards wrecked on the southern shoal and were deemed total losses. These two wrecks resulted in the United States Lighthouse Service (USLHS) taking up the conversations once again of constructing a light on the reef.

Portion of NOAA Coastal Chart #14881 of Lake Huron. The numbers denote the depth of water in feet.

On March 3rd, 1869 Congress finally approved $100,000 to begin plans for a light. In May that year two iron can buoys were placed between the two shoals along the ridge in sixteen feet of water, and in July a crew departed Cheboygan and completed their survey of the reef that month. Over the course of the fall blueprints were drawn and supply contracts formed for the construction. Ironically, in September 1869, the Nightingale wrecked on the reef exactly where the lighthouse was to be constructed.

The United States Government had purchased an island in the Les Cheneaux island chain (appropriately named Government Island), near Cedarville, Michigan, for use as a base of operations for construction of Spectacle Reef light. A work camp was established on the Northeastern portion of the island along Scammon’s Harbor (now Cove) in April 1870. This camp would go on to be used for nearly every offshore light construction in the Straits of Mackinac. A crib measuring ninety-two feet square and twenty-four feet tall was constructed using twelve-inch square timbers and contained a forty-eight foot square opening in the center where the tower would be located.

On July 18, 1871 the flotilla of vessels left Scammon’s Harbor around 8 p.m. for the reef. The vessels included:

Tugs Champion and Magnetic: these two pulled the cofferdam

USLHS tender Warrington: carried 80 workmen

Schooner Belle: carried 60 workmen, would be used to house workmen and as a kitchen

Tug Stranger: pulled material barges Ritchie and Emerald.

Tug Hand: pulled two USLHE barge that carried 1550 tons of stone. This stone would be used to fill and sink the cofferdam.

The work party arrived at the reef around 2 a.m. on July 19, 1871. The wreck of the Nightingale was removed and the cofferdam was placed at dawn. Construction began with the sinking of the cofferdam onto the reef. While some of the work crew labored on turning the cofferdam into a pier, complete with buildings and machinery needed for construction, a team of workmen sank pilings within the opening of the cofferdam to match the contour of the reef. Once complete, a team of divers used rope soaked in tar to caulk the gaps between the pilings and the reef. In September 1871 the work crew had the pier built up 12 feet above the lake level and had completed the needed buildings. On October 14, 1871 the cofferdam was pumped dry and work began to level the shoal for the base of the tower.

On October 27, 1871 the first course of stone was complete. Only one additional course would be completed that year before the weather would end the construction season. Over the course of the stormy fall and early winter, two men were left on the work site. They lived in a shack measuring eight feet by eight feet and tended a 4th Order Fresnel Lens and a steam fog whistle and were, much to their relief, taken back to shore in mid-December at the close of navigation that year. Work would resume on May 3rd, 1872 even though the ice would not be removed until the 20th of that month. Over the 1872 season, one course of stone could be laid in three days following cutting and shaping. By October, the lower portion of the tower and five courses of the upper were complete.

September 28, 1872 saw a storm blow up that caused a great deal of damage and setbacks in construction. Per logs of the construction supervisor:

“The sea burst in the doors and windows of the workmen’s quarters, tore up the floors and all bunks on the side nearest the edge of the pier, carried off the walk between the privy and pier, and the privy itself, and tore up the platform between the quarters and the pier. Everything in the quarters was completely demolished, except the kitchen, which remained serviceable. The lens, showing a temporary light, and located on top of the quarters, was found intact, but out of level. Several timbers on the east side of the crib were driven in some four inches, and the temporary cribs were completely swept away. The north side is now so filled up that the steamer can no longer lie there. A stone weighing over thirty pounds was thrown across the pier, a distance of 70 feet; but the greatest feat accomplished by the gale was the moving of the revolving derrick from the northeast to the southwest corner. At 3 o’clock in the morning the men were obliged to run for their lives, and the only shelter they found was on the opposite (the west) side of the tower. The sea finally moderated sufficiently to allow them to seek refuge in the small cement shanty standing near the southeast corner of the crib. Many lost their clothing.”

Stone work would not be completed until September 1873, with work on the interior of the tower lasting another month. In May 1874 crews arrived to paint the interior of the tower, furnish the station, construct chimneys and install the 2nd Order Henri-Lepaute Fresnel Lens. The lens produced a flash every 15 seconds that alternated red and white visible for 17 miles.

Spectacle Reef is an engineering marvel of its time, and its $406,000 price tag proves it ($9,181,191.40 in September 2020). Based on the 1855 built Minot’s Ledge Light in Massachusetts, the plans for Spectacle Reef called for a granite tower rising out of the lake on the Southern edge of the Northern shoal in about 11 feet of water. The contract for the granite was signed for a quarry near Duluth, Minnesota. However, shortly before construction started the quarry failed to honor the contract, and thus limestone was procured from a quarry in Marblehead, Ohio.

A Perspective of the interlocking blocks cut to make up the base of Spectacle Reef

The stone was transported to Government Island where it would be cut and shaped into the pieces needed for the tower, with final shaping completed at the construction site. The bottom course of stone is anchored to the reef itself using iron pins, measuring 2 ½” in diameter and 36” long sunk 21” into the reef, with each additional course anchored to the previous using pins 24” long. The holes for the pins were then plugged with Portland cement. This, as well as the mortar used, fused the limestone blocks together forming one massive monolithic structure.

Each course of stone measures two feet tall, with each piece of stone being carved in a manner to make it interlock with the ones surrounding it. The design of these pieces is done in a way so no stone can move and that the force of the waves pounding against the tower actually makes it stronger. The lower seventeen courses are solid stone, with a center opening for a well. The upper portion of the tower contains five rooms with a diameter of fourteen feet as living quarters, as well as a pedestal room and lantern room. The walls of the tower at the base of the living quarters measure 5’6” thick tapering to 16” at the top. Unlike most light towers made of brick, where there is an inner and outer wall with an air gap, Spectacle Reef is solid stone throughout. A lining of brick was placed in the upper portion of the tower, to which a metal lath and plaster are attached. The completed tower rises 97 feet above the reef, with a focal plane of 86 feet above the water depending on the lake level.

Spectacle Reef in 1902 with tender ship

The completed station included two fog signal buildings that each housed a ten-inch fog whistle, two cranes (one each on the NW and SE corners), and a boathouse. The station would receive a new fog signal in 1906 with a steel fog signal building as well as a new boathouse. The steam whistles were replaced with a type-C diaphone fog horn on April 14, 1925.

The start of the 1883 season resulted in a tragic accident. Keeper William Marshall and his three Assistants, Edward Lasley, Edward Chambers, and William’s son James Marshall, set out for the light in a sailboat on April 15, 1883. Two miles out from Bois Blanc Island the boat capsized and the four men clung to the overturned boat. Eventually, the crew drifted near the Bois Blanc Island lighthouse where Keeper Lorenzo Holden and brothers Joe and Alfred Cardran spotted them and attempted to rescue the Spectacle Keepers. Their boat too capsized. Joe swam the overturned boat and both Marshalls to shore, while Alfred bailed out the boat and rescued Lasley and Chambers. Both Lasley and Chambers suffered injuries, with Lasley being in very poor condition. William Marshall was nearly frozen and Holden’s family covered him with multiple blankets and rubbed his feet for five hours to try to regain circulation. James Marshall, who had only served one season in the Lighthouse Service and did so alongside his father, sadly did not survive.

Both of the Cardran brothers were awarded a gold life-saving medal on June 7, 1883 for their bravery and both later went on to serve as Assistant Keepers under William Marshall at Spectacle Reef.

In 1896, David D. Spaulding accepted a position as Assistant Keeper at Spectacle Reef, and left his farm and job as a Surfman at the Lifesaving station on Thunder Bay Island. On November 10, 1896 he sailed to the light after stopping by the Poe Reef lightship to visit some friends. As darkness fell a storm blew up, and while pulling up his anchor to reposition the boat to dock at the Light, he fell into the lake and drowned. The boat eventually washed ashore and was found to have a hole three feet wide and seven feet long in it. David’s body however, was never recovered.

Over the years, multiple repairs had to be made to the crib surrounding the light, as it was merely the wooden pier leftover from the construction of the light. On October 2, 1888 $15,000 was awarded for repairs, which were completed from May to September 1889. In 1901, it was discovered that the pier could not be repaired any longer, and $54,000 was appropriated to construct an oval pier made of concrete on March 3, 1903. Construction started April 28, 1904 and completed in 1906, with a square pier costing $98,000.

In 1912 the oil used to fuel the lamps was changed to incandescent vapor (mercury vapor). This gave the light 84,000 candlepower during the red flash, and 340,000 candlepower during the white, making the light visible for 28 miles.

In 1920 repairs were again needed on the crib, with two feet of additional concrete poured surrounding the crib over the 1922 and 1923 seasons. Leudtke Engineering drove 110 steel piles into the shoal around the crib in 1934 to act as additional protection against the ice. The ice often would be over two feet thick surrounding the light over the winter, and would prove to be problematic. In December 1927 the keepers were trapped for four days due to ice encapsulating the lighthouse. They would be rescued on the 14th of the month by the Poe Reef Lightship, which was returning to Cheboygan for the winter. The keepers had to lower themselves out of the fifth-floor window, down a rope and across the ice to reach their boat home.

Spectacle Reef 1970 - Richard LeLievre opening light, cutter Sundew

The late 1940s saw some changes come to the lighthouse. The crane on the southeast corner was removed, the oil house demolished, and the boathouse and fog signal building were both painted white with a red roof. This paint scheme is how the station appears to this day.

Sargent William Wyman, a former Air Force pilot, was flying from Saginaw, Michigan to Kinross Air Force Base (now Chippewa County International Airport) on February 22, 1959 when his plane went down in Lake Huron a few miles from the lighthouse. A search was conducted but ended on March 3rd with no sign on Wyman. In April, the keepers went out to open the light for the season on April 8th, and found a note from Wyman. He explained that his plane had gone down:

“I tried to make it in but could not stretch my glide this far,” Wyman Wrote. “I landed in the water. I did not try to land on the ice as it did not appear to be thick enough…the plane went down within two minutes. But before it did it floated close enough to an ice floe for me to jump. The ice was not over two inches thick. Another large body of water separated me from the lighthouse, so I waited. Suddenly the wind shifted to the northeast and the ice I was on started to move. At the very last moment one corner of the ice grounded against the ice packed around the lighthouse.”

Wyman also apologized for eating their food and leaving the station a mess, and that he had tried to start the generators to operate the radio but was unable to do so. He also explained how he had tinkered with the stations winter light to try to garner attention. The last lines of his message stated that he was leaving to hike across the ice for the mainland. No sign of Wyman was ever found. Eyewitness accounts later show that residents on shore noticed the odd light coming from the lighthouse and had reported it to the Coast Guard, but seemingly too late.

The 1959 season also saw another tragedy when Keepers Cyril Jones and Joe Gagnon were swimming merely ten feet from the crib when a wind blew up and swept them both out into the lake. Jones drowned, leaving behind his wife and five kids.

Richard LeLievre would be the final Keeper of Spectacle Reef. He was stationed at the light from 1970-1972. During the opening of 1970, he and his crew had to cut through five feet of ice to reach the front door of the light, and it took four days for the furnaces to get the interior of the light up to 65 degrees. He noted that the last bit of ice finally melted off the northwest corner of the crib on July 1st, 1970. LeLievre would close the station in 1972 and oversaw its automation. It was at this time the boathouse was demolished and the station was emptied of all furnishing and utilities. The Fresnel lens, however, would remain in place until 1982 when it was replaced. Today, the lens is on display at the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo, Ohio and the current light is a modern red LED that flashes once every five seconds.

2nd Order Fresnel Lens of Spectacle Reef